If you purchase an independently reviewed product or service through a link on our website, SheKnows may receive an affiliate commission.

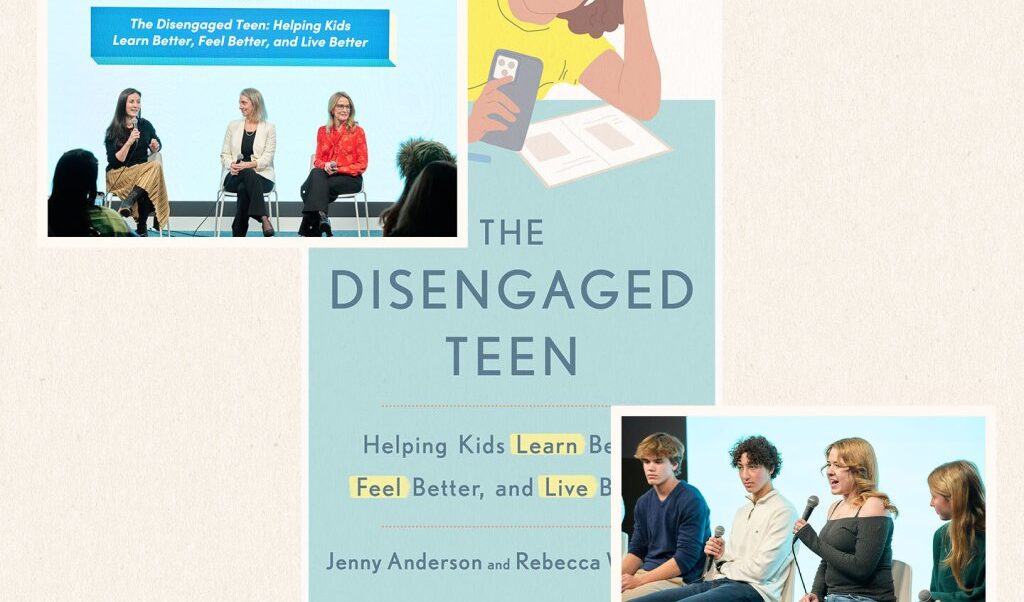

Parents of teens know that getting them engaged in learning can sometimes feel like pulling a mule uphill. And to help us understand why — and, more importantly, what we can do about it — SheKnows hosted a live event featuring the insights of Jenny Anderson and Rebecca Winthrop, authors of The Disengaged Teen: Helping Kids Learn Better, Feel Better, and Live Better, and a panel of four teens, including members of our own Gen Z Council. It was an enlightening look at what Anderson and Winthrop call a “disengagement crisis,” and their expert take on how to tackle it. You can watch the entire video above, but we’re highlighting some key points of the event here.

In their research, the authors found that more than 65 percent of high school students today report feeling “checked out” of school. There has always been a disengagement crisis (have you seen The Breakfast Club?), but what has changed is the impact of that disengagement. If they’re not engaged in learning, it’s going to be harder for them to develop the skills they need in this ever-changing world of technology — and the consequences of this, say Anderson and Winthrop, are “profoundly alarming.”

The authors explained that kids engage in ways that you can’t always see, and that grades only tell half the story. In reality, there are four distinct modes of engagement:

- Passenger Mode: Students who do the bare minimum, often procrastinate and disengage from learning.

- Achiever Mode: Students who strive for excellence, but may become fragile learners due to fear of failure.

- Resister Mode: Students who actively resist learning, often due to feelings of disconnection or frustration. Students in resister mode are typically labeled as “the problem child.”

- Explorer Mode: Students who take initiative and pursue learning with curiosity and passion.

Still, Anderson stresses, “This is not an exercise in trying to pigeonhole kids.” Kids can flow from one mode to another, even within a single day. Driving is a good analogy; In the course of one car trip, you change lanes, coast, and adjust speeds. It works the same way for kids who are in and out of these learning modes, sometimes multiple times daily.

The ideal mode, Anderson and Winthrop explain, is Explorer Mode. Allowing students agency and choice in their learning, and letting them pursue the things that interest them, can foster engagement and motivation. This can then help them develop proactive learning skills that they’ll need to function optimally in the real world.

The Disengaged Teen: Helping Kids Learn Better, Feel Better, and Live Better

As parents, it’s on us to balance the desire for academic success with the need to prioritize our kids’ well-being and mental health. As Anderson cautions, “The system is insatiable. It will never stop demanding things of your child.” So it’s essential to help students build balance. We should actively encourage them to take their foot off the accelerator, she says; let them know that their well-being matters more than their GPA or getting into a certain college.

What else can parents and educators do to support students? First, lean into the content of their learning, rather than just the outcome (i.e., grades). Ask about their interests and passions — even if it’s as simple as, “How was lunch?” Provide as many opportunities as you can for them to explore the things they’re interested in.

Of course, who better to consult for opinions on school (and why they’re not into it) than students themselves? The teens of SheKnows’ Gen Z Council had a lot to say on the topic, and four students — Clive, Santiago, Chloe, and Greta — joined the authors on stage to share their own experiences.

Clive says bad grades don’t inspire him to do better, they just make him lose motivation. For Chloe, the worst is feeling attacked when her parents bring up a bad grade: “It’s about the ten other things you’ve got going on, on top of that test, and it can really feel overwhelming when someone nitpicks about one specific part of your life [where] you might not be doing that well.” Santiago wishes parents knew how much stress can affect students. Echoing this, Greta says that parents don’t understand the extent of the pressure students can be under, and the feeling of having to be “on” all the time.

Winthrop expands on that, saying that kids need “radical downtime.” It’s scientifically proven that they need breaks, she says: “It’s not a bad work ethic. It actually reenergizes you, makes you able to sustain effort longer.”

A running theme in all the research, says Winthrop, was that when kids are allowed to be in Explorer Mode, they get the best grades. (“This was 35 randomized controlled trials in 14 countries, including places like South Korea which are highly authoritarian and have extraordinarily high expectations,” adds Anderson, “so you don’t have to compromise expectations to give agency and choice.”) When teachers give students some freedom and choices about how they want to work, those kids get the best grades.

So what does all this boil down to? By recognizing the importance of agency, choice, and mental well-being in learning, we can help our teens cultivate a love of learning that extends beyond the classroom. By giving them the freedom to explore, create, and take risks, we can help them develop the skills, motivation, and resilience needed to succeed in an ever-changing world. Ultimately, as Anderson and Winthrop tell us, it’s time to rethink our approach to education and prioritize the unique needs and interests of each student — empowering them to become active, engaged, and lifelong learners.

Hear more in our video of SK Conversations’ The Disengaged Teen event above.