But, again, in the back of the bus only 18 hours later, that feeling has fled, or at least faded. He tells me how the waiting that tour entails might be the hardest part, how it feels like wasted time. The stress of logistics, the string of new faces, the unknowns of a new place: “I feel like I’m not built the best for this sort of thing,” he says, shrugging, as if stuck between apology and explanation. “I feel like I do this to keep doing the part that I really like. Working at home by myself is my thing.”

During the pandemic, his under-construction studio became his sanctuary as the world and his marriage wobbled. He worked there before it even had a door, first finishing a Remi Wolf remix that impressed his son by landing on Fortnite. (Lennox is a longtime gamer; Jamie, 14, often kicks his ass.)

He tells me about the mammoth acoustic door he ordered from Spain and finally installed in August, just before band practice began in a neighboring rehearsal room in September. When it arrived, as he and a pal struggled to carry it across the street, two Lisbon strangers hopped in to help. When one guy let go too early, the door smashed Lennox’s finger against the ground, breaking it. The pain was excruciating, but he didn’t miss band practice. He doesn’t resent the door, by the way. “It locks,” he says, his tone pure celebration.

In an ideal world, he continues, he could work there forever in private—yes, writing his own music but mostly adding bits to tracks people send him, the thing at which he insists he’s best. But he instantly backtracks, at least a little. He knows what it’s like to be isolated and the damage it’s done before, whether in boarding school or Lisbon. He talks about leaving Lisbon now, how moving back to the United States would make it easier to crack jokes, since his Portuguese has never been very good. He tells me about the idea of working more with Dibb in a kind of production tandem, since Dibb has the technical skills he lacks (and since they’ve kind of been doing it all their life.) He tells me, in essence, about that endless and vexing toggle between connection and concentration, between shaping the world and being shaped by it.

“Living in New York after Boston taught me how to relate to people, to be comfortable talking,” says Lennox, who still hasn’t applied for Portuguese citizenship after 20 years there. “I feel like I’ve gone to ground zero of not being able to deal with people. I can do it again, if I come back here.”

I finally remember to ask Lennox why I’m on his bus at all, a thing several of his friends wanted to know. So many of them were astonished that he had said yes, letting a relative stranger break his bubble of privacy. Animal Collective says no to this stuff almost as a rule, and everyone expected Lennox to do the same.

He first tells me it was because we knew each other, anyway, and that he’d had a positive experience with the writer Philip Sherburne, a mutual friend who spent some time with him for a Pitchfork profile a decade ago. But I’ve been told by his buds to ask this question and even press a little, because there has to be more. At last, he gets there.

“There has been something I have been fighting against in myself since that high-school time, a puzzle I couldn’t solve. Maybe I was in denial about it for a long time, but I couldn’t ignore it anymore,” he says slowly, feeling his way forward as if looking for a light switch in an unfamiliar room.

“This whole period has been about confronting something about myself—wanting to please everyone all the time, maybe,” he continues. “You spend your whole life trying to reconcile whatever happens to you when you’re young. Perhaps this was my time. It felt like, ‘Figure it out, or oblivion.’”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

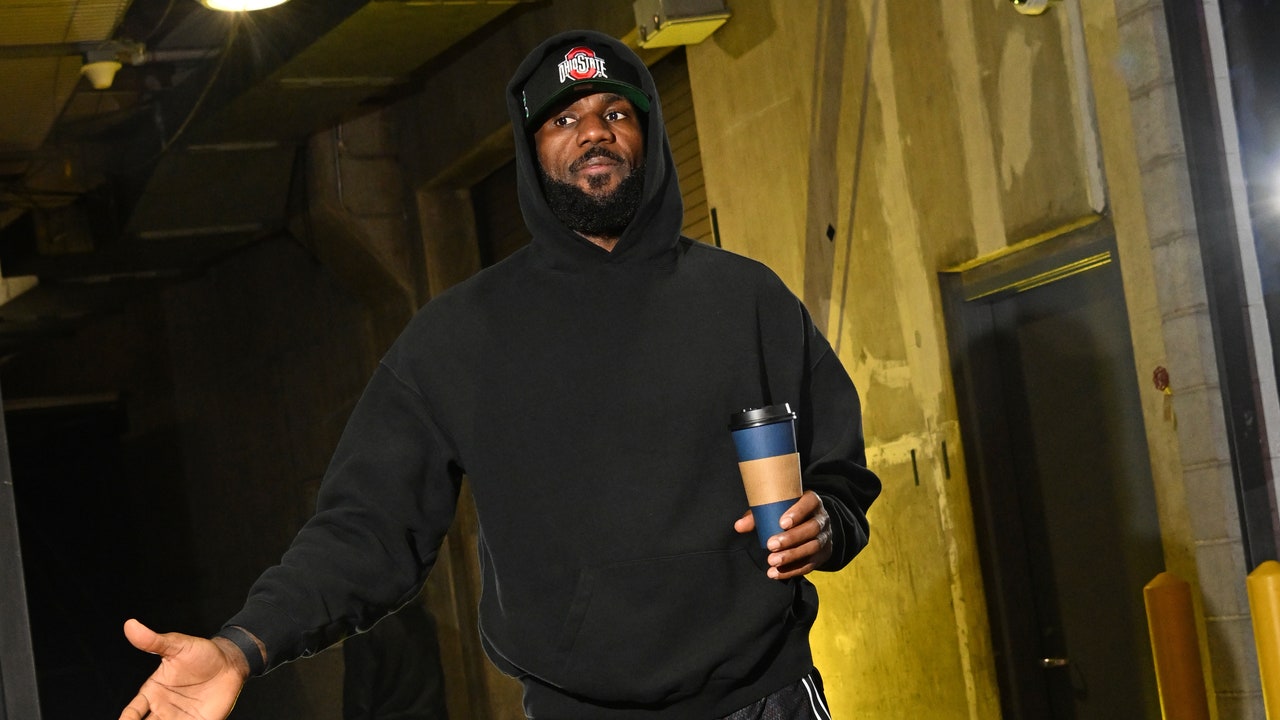

Photographs by Asger Carlsen

Grooming by Laramie Glen at Day One